Bypass .NET Request Validation with MSSQL

So - once in awhile I see applications with this specific flaw and I find myself just trying to jog my memory about this faint thing I remembered in an application. I figured sometimes to retain this information you just need to get it out of your head and into another place - like a blog.

For this blog post, I wanted to share just a simple bit of information I've needed from time to time for bypassing character restrictions on .NET applications using web forms. So, the long and short of it is that there's something called request validation in .NET applications, and in older versions of .NET or let's just say - more homebrewed/homemade kinds of .NET applications this is usually implemented in a lacking way - especially if the application is using MSSQL.

Homemade things have their charm and place, but maybe not so much for enterprise software which contains highly sensitive PII... just saying.

With that being said even though this is referencing older applications - I saw this kind of broken request validation very recently on a new application which had some fancy rebranded functionality on the surface - but was still an old .NET application to its core doing dumb stuff in the backend database.

Ok fine, so how do you beat form level request validation performed by .NET? Typically, by just using different unicode characters which will be translated by MSSQL and stored in a database as something different. I sort of imagine the servers having this kind of conversation among themselves.

Interconnected systems are always so positive and upbeat.

Got it? Cool, let's dig into the specifics. Let's say you save the following text to a form with this validation turned on:

<txt1>

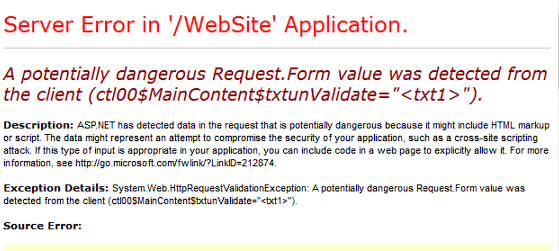

More than likely what you'll get is this:

I stole this screenshot from: Request Validation with ASP.NET 4.5 : A deep dive | Code Wala, didn't want to put my own here.

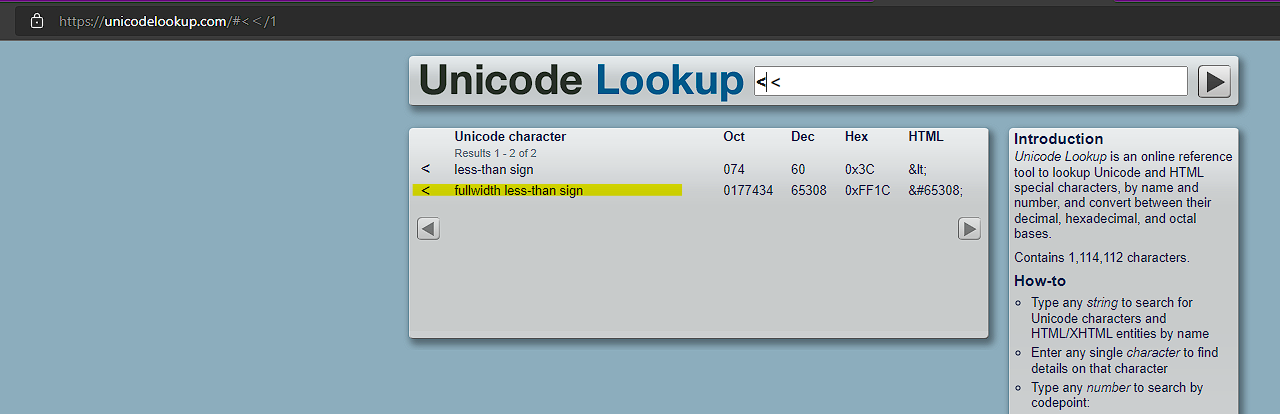

Ok, neat. So we're screwed right? Not yet. You see there are different kinds of opening and closing brackets which will bypass field validation but will get translated. A perfect example of that is something like this unicode character:

<txt1 >

So they look the same, but they're not the same character. If we go to our trusty Unicode lookup tool (literally unicodelookup.com) you can see we have char 1, the less-than sign, and then char 2, the fullwidth less-than sign.

The first one gets blocked, the second one doesn't, gets written to the database and then MSSQL converts char 2 into char 1 through a process (which I believe is related to collation - not 100% sure on that one). How nice of it.

So this doesn't work everywhere... but - it works a whole lot and instead of hunting for this info every time I need it I figured I'd write myself a little something on my blog so I remember for next time.

Maybe you'll find it helpful too.

-Marbaṩ